Hello friends!

Well.

Premium readers received a blast straight to their inbox yesterday morning headlined ‘Disaster averted in Myanmar, for now’ at 9 am Canberra time, or 4 am in Yangon.

Around that time Aung San Suu Kyi and scores of Myanmar’s political leadership were placed under arrest by the military, known as Tatmadaw, in the country’s first coup since 1988.

There’s going to be a lot of brilliant analysis in the coming days but today here’s some first response reads and tweets showing us where we’re at 24 hours later.

I’ll be back later in the week with more.

Stay safe out there

Erin Cook

Aung San Suu Kyi, as well as President U Win Myint and chief ministers from states across the country, were taken into custody. I’ve seen lists of other people, including Members of Parliament who were meant to sit Monday and activists, but I can’t find much in the way of official confirmation just yet.

Victoria Milko for the AP has a piece here with a fantastic look at the constitution and especially Article 417, which gives the military approval to intervene in times of emergency. Military TV has said the COVID-19 pandemic and the civilian government’s holding of the election in November were the emergency which has gotten us here.

Elsewhere I really got a lot from the Reuters backgrounder and don’t forget my own one from the weekend!

Still, if you only read one thing today, make it this piece from Frontier Myanmar (and you better subscribe!)

The Tatmadaw has seized executive, judicial and legislative power for a year, said a military statement this morning, following the overnight arrest of senior government leaders, including State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President U Win Myint, and the chief ministers of Myanmar’s states and regions.

The statement that was broadcast on Tatmadaw-controlled media shortly after 8am cited article 417 of the constitution, which permits a military takeover in the event of an emergency that threatens Myanmar’s sovereignty, or that could “disintegrate the Union” or “national solidarity.”

So the military is mad, but why exactly? Analyst David Mathieson has one theory, according to the Washington Post. ‘There is a “disdain that the constitutional legal system the military established was working so well for their nemesis Suu Kyi: the landslide election was a clear rebuke to them coming back to power. So, when you're unpopular and increasingly irrelevant, you scupper the apparently sweet deal you have for your institution.”’

For many generations in the country, as well as analysts, Monday looked all a little too familiar.

Thinzar Shunlei Yi posted some eerily quiet footage of Tatmadaw officers searching a National League of Democracy office in the city of Pathein:

Thailand’s government isn’t too interested in getting involved:

As Phoebe, of Good Films Only, points out, this is what the system is designed for:

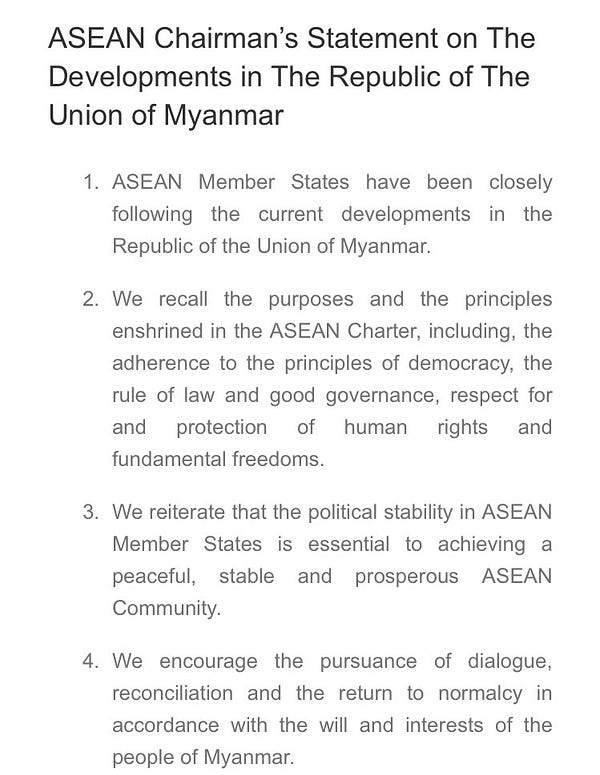

Asean itself says:

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen is a little more explicit:

Malaysia is an outlier, leaning on Asean’s peace and stability remit instead. This is, of course, complicated by the country’s own declaration of Emergency and accusations of conducting a coup by suspending parliament under the guise of public health measures.

Still, for all the talk of Asean values and the like the reality is, it’s a very inter-connected region and even more so in the Mekong states. Myanmar’s Embassy in Thailand was Monday afternoon expecting anti-coup solidarity demonstrations:

The demonstrations, attended by both Myanmar nationals and sympathetic Thais, ended in the now common face-off with Police:

Elsewhere, countries whose embassies last week issued statements calling for the respect of democratic norms and safety in the country have followed that up with strong rebukes. It’s still very early in the piece and I imagine foreign ministries across the West are debating how to respond.

The Irrawaddy is compiling statements from around the world here. Notably, China and India have both issued statements — India far more interested in upholding democracy than China, of course.

Hunter Marston has a bit more context here for incoming China takes:

The US has come out of the gates swinging. “The United States removed sanctions on Burma over the past decade based on progress toward democracy. The reversal of that progress will necessitate an immediate review of our sanction laws and authorities, followed by appropriate action,” President Joe Biden said in a statement.

Like so many people watching this from so far away, I’m so grateful for those working hard in Myanmar to get the word out to the world:

It might just be the beginning:

To be honest I’m not surprised about what happened. Everything was planned. And last night the military put out a statement about the foreign diplomatic missions and we realized they are very angry [about losing the election and the international communities refusal to take their claims of fraud seriously].

I’m not really shocked they did this. But I’m really shocked they cut off the signal. I texted someone last night saying they can do whatever they want, and they have guns.

Myanmar’s Coup: The Aftershocks (Asia Unbound)

Although the army has declared a state of emergency for a year, past history in Myanmar with such declarations could easily suggest that the state of emergency could go on for many years. After all, the Myanmar military still see themselves as the protectors of the country, despite several years of shaky democracy, and they wrote the current constitution, which has a clause that essentially allows for a coup and still gave the military significant powers.

The army may have become afraid that Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) would be able to consolidate more power after last November’s elections and cut back the army’s power, that if the army commander retired he could become vulnerable to international prosecution for the army’s actions and might not be able to protect his family’s positions and wealth, and that at some point in the future Suu Kyi and the NLD might be able to change the constitution and diminish the power of the armed forces.

Since November, the armed forces have been disputing the election results and claiming they were fraudulent.

Myanmar’s military reverts to its old strong-arm behaviour — and the country takes a major step backwards (The Conversation)

Indeed, this power-sharing arrangement has been extremely comfortable for the military, as it has had full autonomy over security matters and maintained lucrative economic interests.

The partnership allowed the military’s “clearance operations” in Rakhine State in 2017 that resulted in the exodus of 740,000 mostly Muslim Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh.

In the wake of that pogrom, Suu Kyi vigorously defended both the country and its military at the International Court of Justice. Myanmar’s global reputation — and Suu Kyi’s once-esteemed personal standing — suffered deeply and never recovered.